Without conversation, what else could we do in the winter months? When the earth is covered in snow, people are forced to stay indoors for long periods in small spaces. In the long winter nights of Northern Europe people created stories full of vivid imagery and feeling. We see this in Svetlana Boym’s collection of essays, “The Future of Nostalgia,” when she tells of Russian intellectuals who kept warm in the long winter by burning books. The aristocracy became intoxicated by this type of absurdist, poetic sentiment.

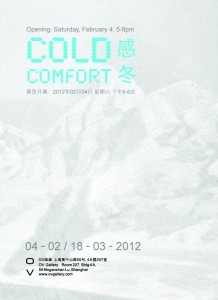

The long wintertime makes room for narration. Take, for example, Liu Changqing’s poem “Seeking Shelter on Lotus Hill on a Snowy Night” when he describes returning home in the dark, through wind and snow as dogs barked at the gate. Another famous winter narrative is that of the “Panther Head” hero from “Water Margin,” who is nearly killed in his hut in the middle of a heavy snowfall. Winter’s barren landscape gives us the power of creativity, which is the subject explored with charm and innovation in OV Gallery’s “Cold Comfort.”

At the entrance of the gallery is Ji Wenyu and Zhu Weibing’s installation “No One in the Garden of Eden” (2010). Made from white mosquito net with pink borders, it creates a delicate vision of Paradise. The trunk and intricately folded canopy of the tree are shrouded in gauze while its long, exposed roots hang all the way to the ground. Though there are no mosquitoes, flowers, or people, this Eden still seems like a precious place.

Monika Lin’s “Take Away” (2012) installation is a miniature vision of nature. Tape is used to create withered trees made of rice and masking tape which are encased in resin. These tiny, inexpensive life forms can only escape their fleeting fate once they are set in hard resin. This work explores themes of waste and rapid consumption. Chen Hangfeng’s video-installation, “It Comes and Goes” (2011) investigates similar environmental concerns while lingering between the territories of dream and reality. A prism shows the shape of a snowflake, but the details are made from blue, commonplace objects: cars, superman toys and cleaning products. Paradoxically, these cleaning products completely conceal the spotless white background.

Shi Jing’s “White Line” (2006) series 4-6 humorously examine the power of light. Approaching the painting from different perspectives changes the image and ultimately the meaning of the work conveyed to the viewer. From the front, one sees ambiguous shapes and the linear texture of the paint. But when standing to the left or right, the viewer gets a clearer picture: one of a glacier, an ocean and melting ice.

Wang Taocheng’s work “Sister” (2010), on the other hand, offers a mysterious unofficial history transcribed onto a scroll. An anonymous narrator tells the story of the disappearance of a young student. The artist does not draw attention to the floating body in the pond, but rather a flower magically rising on campus. The story, though simple, is powerfully chilling and cold.

The works of Chen Xi are reminiscent of children’s dreams, especially the dry planet and flowers of “Moon Light,” (2011) which are evocative of Saint-Exubery’s “The Little Prince”. Meanwhile “Icebreaker” (2011) takes advantage of the correlation between white paper and ice. A small boat gashes through the white canvas, leaking a trail of blue ocean in its wake.

The show reminds us that winter is full of possibility and mystery which lies just below the barren landscape. Just as with “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” when Colonel Aureliano touches the ice and says without hesitation that it is hot: sometimes winter can be surprisingly hot.