Hurtling Through Space and Time: Shi Jing’s Existential Explorations

By Rebecca Catching

Shi Jing has long been interested in the concept of time and its passage. His previous series “White Line,” for instance, embodies this idea using a series of icebergs taken from photographs. An iceberg offers us a visual representation of time’s passage as it shrinks dramatically over the course of years, months and sometimes as quickly as weeks — its form evolves like the waning shadow cast by the arm of a sundial.

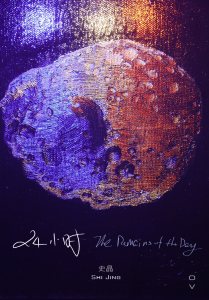

His asteroid series takes this concept of elapsing time to a new and cosmological level. Images of asteroids, which were taken from an Internet fan-site, are applied to the canvas using a combination of brushstrokes moving in different directions to depict the bulbous, pockmarked forms. What fascinates Shi Jing is the idea that for an asteroid, travelling an average of 90,000 km an hour, these photos are outdated even by the time they are taken. What we perceive is merely an image of an asteroid which is now light-years away from where it once was.

Its appearance may be slightly smaller, chunks may have broken off or it may have burned itself up while entering the atmosphere of another planet. Buddhists often mention the concept of “ksanas” when discussing time. A ksana corresponds to 1/75th of a second and in that time it is said there are 900 instances of arising and ceasing. This could mean something as simple as a seed sprouting or an animal dying.

Asteroids have a complicated relationship with other celestial bodies, always bringing with them a whiff of catastrophe and the possibility of bringing about more than 900 instances of arising and ceasing. An asteroid was that was likely responsible for ice age which caused the death of the dinosaurs, and on April 13, 2036 there is the purported threat of Aposhis which could collide with earth if it passes through a gravitational keyhole.

There is also something extremely existential about an asteroid, a cold piece of ice and dust composed of carbon, silica or metals floating aimlessly through space with nothing but a weak gravitational pull to some distant planet to give it a sense of belonging.

Shi Jing highlights this sense of alienation using only black paint, the works are illumined with specialized frames out of which protrude LED lights casting eerie shades of green, blue, yellow and red, which reflect off the texture of the paint.

This cosmological view makes our little planet seem of little import. In the greater scheme of our solar system, galaxy and finally universe, we as individuals are by comparison like specks of dust on the head of a pin, in a box of pins, in a carton of pins, in a warehouse full of pins.

Shi Jing places our earthly activities in this context of insignificance with an installation work where he takes a local a 24-hour news channel and projects it onto a mirror ball which disperses the image into glittery shards of light that dance across the walls. Here he takes the contents of our human lives and disperses it into the dark, creating a glittering galaxy within the gallery — a transformation from a state of “somethingness” (the news channel) to “nothingness” (the small squares of light) as if the contents of the broadcast had been sucked into a black hole.

In a sense, we are all like comets, just passing through our little corner of time and space. Our time on this earth represents merely a small fraction of the 13.75 billion years during which the universe has been in existence. Buddhist scripture describes our existence as being like bubbles on the surface of water; we arise quickly and just as speedily disappear. This notion stands in comparison to other Buddhist forms of heaven, such as Paranirmita Vasavartin Heaven where beings can live for over 25 million years.

In light of the brevity of our lives, Shi Jing gives the viewer a sly wink, a nudge to release themselves from the stress and conflict of contemporary life, a call to enter into a field of completely new possibilities.

In the last part of the show, Shi Jing examines the minutiae of our mundane existence taking a web cam and placing it outside the gallery then projecting the resulting grainy images onto a wall within the space. Thus he completes the whole cycle from asteroids (outer space), news channel (the whole world or earth) to the banalities of life in the small Moganshan Lu community (local and individual). The overall effect is at once humbling (despite our delusions of grandeur, we are all, every one of us, utterly unimportant), but at the same time this is somewhat comforting. It reminds us that all we are required to do is live in the moment, to go about our lives causing a minimal amount of pain to those around us with no pressure to conquer and triumph.