The relationship between culture and power has a lengthy history, from the glory of the Chinese dynasties, to the Egyptians, the Mayans, the Mesopotamians, the Greeks and Romans — these great civilizations all shared highly developed intellectual and aesthetic cultures. There is nothing like great cultural achievements (pyramids, palaces, exquisite ceramics, finely embroidered silks) to inspire awe in those you hope to conquer. And we can find contemporary examples too. Think of the style and charisma of the Nazis (whose uniforms were actually designed by Hugo Boss and whose films were made by Leni Riefenstahl), the influence of colonial architecture in conveying prestige upon the colonists, or the more kitsch but certainly no less impressive spectacles such as the Mass Games in North Korea used to impress the local population. The art world is often at the behest of those in power. For example where would the Renaissance be with out the yearnings of the Medicis to bolster their nobility through an interest in art.

And though the art world is often subordinated by more powerful influences, we mustn’t think of it as a utopian paradise by any means. These same power structures exist within the art world — the Art Review Power 100, the Turner Prize, the Academy Awards and the influence they wield in making and breaking the careers of artists. In this show we’ve invited three artists Li Mu, Bai Yiluo and Zhang Hao to examine the subservient, parasitic and mutually beneficial relationships between power and culture.

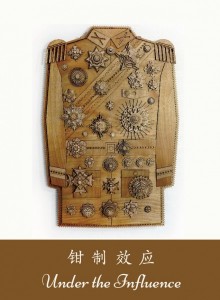

Bai Yiluo creates a series of sculptures which use accumulations of symbols to explore how the individual expresses his role within the hierarchy. It is not so often in life that one literally wears one’s resume on ones’ clothing but such is literally the case in the military where a decorated war hero will sport a number of medals and ribbons which signify his rank within the organization. Royals of course often had certain colors which only they were permitted to wear and primitive societies are known to do the same using horn, bone, feather bead and even body modification in order to celebrate a man’s abilities. Interestingly enough this instinct even filters down to the level of children with groups such as the Girl Guides, Boy Scouts, or in China the badges awarded to primary school students known as yidaogang. These expressions of prestige can even extend to the vehicle one travels in (is it Air Force One or a Spring Airlines jet?), the people who surround the person, body guards, aides and their actions. Do you carry your own umbrella or not? Even a harem could be seen as a symbol of one’s power as it was a way to help the ruler proliferate his genes — an idea that Genghis Khan, no doubt, fully embraced.

Bai Yiluo’s work “Center No.2 ” though it still resides partially in the territory of the abstract exude an aura of power. One figure looks to be something of a general, with a shoulder strap, razor like epaulets and hands and a constellation of ornate medals all over his uniform. These medals in themselves are interesting, composed of several different layers of cog-like figures topped with a symbol such as a cross or swastika. While the forms conjure up the idea of a large political machine with many interlocking parts, the forms are more extreme than regular cogs — something like a cross between a cog and a ninja star — some dangerous object that can impose harm. This composite sketch of power also has monarchic and religious overtones — holding a scepter in one hand and its head surrounded by an array of concentric circles similar to those one might see in a medieval icon painting.

In “Center No.1” the figure is standing square, facing the viewer, its chest decorated with orderly rows of medals. Its head is an even larger ray of concentric circles and evocative of the leaders who have compared themselves to the Sun ( for instance Louis XIV). The figure could very well be a king, seated on a throne raised on a dais. This extends the transfer of power into symbols from the realm of clothing to furniture as well. Thrones were typically used to make a ruler look larger and the dais serves to add an extra level of height so the supplicant is forced to look up. Often an audience with the ruler was acompanied by was a whole set of ritual behaviors of self-abasement including bowing, kowtowing, prostrating, hand and feet kissing.

In the third work, “Center No. 4,” we see the sculpture enter into an almost completely abstract territory and then swerve back into the figurative. The work features two circles which look like a series of circular saws spinning in opposite directions. Between these two saws is a hexagon shaped form. But there is something strange; it seems that one can almost pick out a neckline and a pair of epaulettes and then all of a sudden it becomes clear — there are two identical figures like Siamese twins only lacking legs. Here Bai depicts a megalomaniacal narcissus who has fallen in love with his own reflection. But there is an element of menace in the work as the torso of the figure is so short that the saws seem perilously close to each other, as if they could at some moment crash into each other in a shower of sparks.

These symbols which adorn Bai’s works were designed by the artist on computer and then manufactured in a wood working factory. The wood itself is the same grade used to make packing crates for art works, a fact which further solidifies this relationship between power and culture.

Zhang Hao offers a different interpretation of identity specific clothing in his work “Hat Trick” — a series of drawings in book format the work features nurses, peasants, knights, queens — all with various kinds of headgear. The name hat-trick comes from the sports term meaning to score a goal three times, but also from the idea of a “magic trick” as in how wearing a hat can magically transform the identity of the wearer . . . or perhaps not.

One set of images for instance features Queen Elizabeth and Diana on opposite pages. Both are wearing the same coronation tiara, and as Zhang Hao explains, though both entered Buckingham palace, the two had very different fates. While the queen’s image is framed in a gilded frame, Diana’s visage surrounded by the shape of a tombstone. In between the two works is a blank page with an oval cut out which allows one to see through to next page. When flipped one way, the queen’s golden frame is gone which implies a kind of de-throning. This is also highlighted by the fact that her eyes and nose are blacked out by the words “God Save the Queen/ Sex Pistols” which imply that her status as a revered monarch is on the wane.

He continues this theme of fallen glory with an illustration of a female police officer wearing majestic set of knight’s armor— her face little but a field of black with two eyes. Zhang Hao explains that despite the existence of a Black president, African Americans still live in marginalized state of invisibility. This concept is reiterated in another illustration of a group of peasants doning exaggerated straw hats. But to call them peasants would perhaps be in accurate because they are in fact only black forms beneath the shadows of the hat with few distinct features whatsoever.

The series of 150 drawings explores not only the position of powerful individuals but all the various permutations of power. For instance an image featuring a top hat with a number of hands all reaching to pull out a rabbit likens power to the invisible hand of a magician, so diffuse, omnipotent and mysterious that we have no idea of its identity.

He references this topic again with an illustration which features a number of different codes, for instance the code of the Mason’s — the secret society of American power brokers — telegraphic code, Morse code, braille and the code used by Mary Queen of Scots to send letters in hatching her scheme with Anthony Babington.

Power structures, it seems, weave their roots into every level of society. Zhang embodies this idea in one work called “Official’s Hat Chair” which depicts an official’s hat chair, paired side by side with rotund official donning an exaggerated official hat upon his head. The idea that the form of the official’s hat could be borrowed and incorporated into a chair conveys a sense that the forces of power are so strong they can insinuate themselves into even inanimate objects.

This invisible nature of the power brokers is also conveyed through his “Award Certificate” series. The work tackles the issue of how many circles in China have a chongyangmeiwai “blind worship of the West” attitude which grants awards such as the Oscars and the Turner Prize an incredible amount of influence. It’s very obvious who won the Academy Award for best film, but we pay little attention to who the judges were and how much weight each one of them pulled in the decision making process. He has executed this series using a familiar template — the jiangzhuang or award certificates of the 1950s and 60s. Actually this form dates back to the Qing Dynasty when jiangzhuang, made of silk, and gongpai, often printed on paper or metal, were rewarded to upstanding citizens. As early as the Republican Era we began to see jiangzhuang appearing in a form rather similar to what we see today. In discussing this work Zhang Hao mentioned that these certificates were incredibly important to those living in the 50s and 60s and even today, that generation still treasures their awards clinging to their past glories and the zeitgeist that accompanied them. Whilst young people today are making spoofs — “Beautiful Girl Award” or “Hot Guy Award” — often looking more towards international awards for validation of talent.

Zhang collected over 100 images of these awards which usually featured different permutations of stars, flags, agricultural splendor and infrastructural accomplishments such as bridges. Instead of using the common transliteration of the names of these prizes, he choses new homophonous characters which aim to diminish the prize or poke fun at it. The Pulitzer, for instance, is translated in a way that implies to toss and turn in bed — referencing the fact that the winners of such a prize are usually rewarded for digging into very sticky issues.

For the Oscars, Zhang Hao chose deliberately complicated characters with many strokes which were seldom used, referencing how many Chinese film directors try to show the obscure and exotic side of Chinese culture in order to gain currency with foreign audiences.

By giving them new and often absurd meanings Zhang Hao is trying to nullify their influence and localize their meaning. The Hugo Boss Asian Art Award, for instance, sounds like the name of a local dish. While the Turner Prize problematizes the nationalistic elements of these awards — his transliteration contains the word for yelling, or perhaps one might say crowing — as Zhang Hao feels like the Turner exists merely to sing the praises of British artists.

Li Mu also examines this this transnational relationship between power and culture in his work “Qiu Zhuang Project.” The work began when he visited the Van Abbemuseum as part of the “Double Infinity” exhibition held by Arthub Asia. Originating from a remote village, four hours by bus and taxi from Shanghai, Li Mu, was inspired to introduce the people of his hometown Qiuzhuang to the museum’s collection of classical modernist works. This took the form of taking works such as Sol Lewitt’s “Wall Structure” sculptures and creating copies of it with which the villagers were free to do as they pleased. One man affixed it to the ceiling and used it to hang bird cages housing a number of orange canaries. Another villager inserted panes of glass in the ladder structure and used the frame as a kind of display case for rocks, crafts and souvenirs from his vacation. The sculptures were so popular that some people even began to make their own. Thus rather than the exchange be a one way transfer of culture from West to East, the villagers adapted the works to suit their own needs and uses — thus generating something new.

Unlike other forms of soft power, the goal of the project was not to merely to export foreign cultural products into new markets in order to win influence, rather it was to give a chance to the villagers to be exposed to something different, whether they embraced it or not was irrelevant — any result was equally valid.

Some of the works proved to be quite challenging. For instance “The Lovers: The Great Wall Walk” video performance by Ulay and Abramovic was shown in a family owned grocery store. At first the owners of the store did not really understand the work but in the end they were actually quite proud to have it in their store and volunteered their space for future collaborations.

And while, the project opened horizons for the villagers, it also changed Li Mu’s life as well. He has spent roughly a year in the village and like the generation of youth which was sent down to the countryside during the cultural revolution — it was a process of negotiating city ideas with local mindsets.

As knowledge resources were scarce in the village, he also came up with the idea to create a library filled with donated art books. The project produced a variety of reactions: once an internet repairman was completely (perhaps pleasantly ) shocked by finding a slightly racy art book donated by a professor friend of Li Mu. Whereas Li Mu’s father complained that there should be more books about agriculture.

Again what is interesting about this project from the urbanite’s point of view was how the countryside mindset sometimes clashed with an urbanite’s view of the library, for instance visitors wanting to smoke in the library, play cards, or spit on the ground. The project also raises the question of why we build libraries. Who are we serving? Our own egos, wanting to promote our own sense of “culture” or do we do a disservice to the people by bringing it down to the lowest common denominator and catering to the arguably unsophisticated tastes of the locals?

This sense of exchange also occurred through Li Mu’s invitations of his friends (foreign and Chinese) to visit the village. And for those unable to visit, he has created an extensive blog cataloguing the project.

The project will be brought to a close around Chinese New Year 2014 and therefore the presentation of the work in the gallery somewhat reflects its unfinished nature. Li Mu has produced a number of documentary images of the works installed in situ, which are sheathed in a cloth on which is silkscreened a schematic image of the work. This concept of veiling is aimed at instilling curiosity within the viewer and also represents the duality of the project — the transfer of images of Western art onto Chinese-made cloth which is used to cover up a very locally specific art project. We can hope that in the future the work finds its way back to the West to help reverse the cultural trade deficit, but in the mean time there is nonetheless a transfer of information from the rural sphere to the urban, which is also a valid action given the gaping divide in ideology between rural dwellers and urbanites.