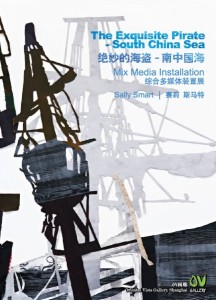

Sally Smart: Pulling Up Anchor, examines shifting ideas about culture and gender in The Exquisite Pirate

By Rebecca Catching

Was there ever a woman who flew the Jolly Roger? Were there ever

ruthless, peg-legged, hook-armed women raiding the merchant vessels of

the South Pacific? It’s a question that inspired Sally Smart to plumb the depths of history – to look deeper into the very gendered figure of the pirate.

The Exquisite Pirate explores a fascinating world of dark and murky themes using a palette of typical pirate imagery, jaunty skulls, rickety ships and saber – wielding pirates hewn from a variety of materials.

Smart’s visual vocabulary is one based on plunder – a culling of photographs from magazines, bits of fabric and strips of stained felt and canvas.

This way her art offers up a triumvirate of meaning with the photographs bringing immediacy, the painted cutouts lending a sense of shadowy abstractness and the use of various fabrics offering a domestic almost “crafty” element to her work.

Smart has long been interested in the idea of crafts as “traditional women’s work” and busies her hands with the task of cutting, staining and sewing the various elements together. Her inclusion of gingham, flowered cloth, brooms, long strips of curlicued decoration and braids, place symbols of docile domestication against piratehood – a decidedly “unladylike” profession.

The artist first became interested in the hidden history of women pirates while watching an animation based on Treasure Island in 2003.

As it turns out, there were indeed female pirates, figures such as

Mary Read and Anne Bonny, English women who entered the pages of history through the accounts of Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of Pyrates (1724-1728). There were other figures such as Irish

pirate Grace O’Malley and Jacquotte Delahaye, who practiced her trade in the Caribbean. Even China has a history of female pirates, women such as Cai Quin Ma, T'ang Ch'en Ch'iao or the infamous Cheng I Sao – a former prostitute who married a pirate and built her own empire of piracy, blackmail and protection schemes in the South China Sea.

Smart’s work, however is also inspired by fictional, namely a performance in Melbourne in 1997 by Kathy Acker, who performed excerpts of her book Pussy King of Pirates. The book chronicles the lives of two swashbuckling prostitutes who hire female pirates in a quest for booty. The novel both erotic and absurd filters its way into Smart’s work and spreads into a number of themes, everything from colonialism, to instability, to memory, the body and gender.

Smart states, “Acker uses the metaphor of female pirates to explore feminine issues and sexuality, at the same time subverting the historic perception of piracy as a male domain.”

Piracy is in a sense an exercise of power – and women usually end up on the wrong side of this power dynamic. Smart’s work is full of images which suggest rape and plunder – for instance a cut out silhouette of a severed head with a few loops of photographed braids dangling from the nape of the neck.

But in other scenes the pirate is cast as a menacing chimerical figure with a fat grey braid escaping from a polka-dot kerchief. Her chest features no less than four breasts (female pirates were often depicted shirtless in historical illustrations), while her pantaloons play host to four legs – two of which are wearing multicolored tights and strappy dominatrix heels. Another gender-bending pirate wears the typical tri-cornered hat with a composite magazine clipping face. Her mug bears both male and female features, all overlaid with a black cut out of a goateed grimace.

Both Bonny and Read found their way onto boats posing as males and though Smart wants to in no sense glorify female pirates, she is making an attempt to turn this power dynamic on its head by placing women at the stern.

But Smart goes beyond gender, using boats to convey a variety of cultural and political messages. The role of the pirate has strong links to colonialism – the plunder of land and resources, the spiriting away of treasure, enslavement of captives and the lock-stock-and barrel exploitation that accompanied such landings.

It was boats that brought prisoners to Australia and which brought settlers who caused strife amongst the Aborigines. Smart’s haunting vessels, outlined in stark black are trailed by a light grey afterimage – which hangs behind the boat like the remains of a grudge.

Boats also figure into modern history – symbolizing the narratives of desperation, of the ongoing problem of smuggled of Asian sex workers, or of the 2001 Tampa refugee incident where asylum seekers were stranded on a boat weathering the political debate which raged on land.

Boats represent not only the continually changing cultural fabric of Australia, but also its growing awareness of its neighbors. Smart herself has had a continuing intellectual interest in the art of Asia Pacific. Her work has been exhibited from China to Indonesia, and it was there that she developed an interest in Balinese Wayang Shadow Puppets and built her own collection.

Smart, however, is equally fascinated by the maritime culture of the

Asia Pacific region, “I visited the Darwin Museum and Art Gallery, in

late 2004 – it housed a Museum of Boats – the boats from the region of Oceania and Asia primarily. I was fascinated by some of the boats, the scarification and tattoo-like markings along with various decorative, feminine gendered elements. At this time issues of immigration were at the forefront of Australian political life. The boat/ship was looming as a sign of relevance in contemporary and historical Australia,” says Smart.

One of the most interesting things about Smart’s work is that it is not firmly anchored to a single reading. Many of her scissored forms possess purposefully vague contours, which allow her shapes to take on alternate meanings in the mind of the viewer. Like a Rorschach drawing they waver and morph as the mind flips between different readings.

What at first looks like a sea monster with a gaping maw soon turns into a large body of land swallowing up an island – a visual exploration of colonialism and land acquisition.

Even the forms themselves are not permanently joined together, but fixed loosely with pins. Like a cartographer, Smart employs a system of grids in order to properly map the space and position the cut outs. This way, she is both physically and conceptually constructing new identities.

In a sense Smart’s shape shifting forms and their unstable relationships, act as a metaphor for our fluctuating social attitudes about gender, culture and identity. Her work creates for us a kind of socio-political Bermuda triangle, where we lose our bearings and all of our traditional navigational systems cease to function.

Sally Smart: Artist Statement: The Exquisite Pirate

The Exquisite Pirate is an ongoing body of work, begun in 2004. It has been exhibited as wall installations of varying dimensions and is made primarily from felt, canvas, silk-screened elements and everyday fabrics.

The Exquisite Pirate work has developed from a long-term interest in representations of feminine identity with reference to contemporary and historical models. It also brings forth the woman pirate as a metaphor for contemporary global issues of personal and social identity, cultural instability, immigration and hybridity, and reflects on the symbolism of the ship and its relevance to postcolonial discourse and, specifically, its relevance to contemporary and historical Australia. My work places a practical and theoretical emphasis on the installation space, on mutable forms and methodologies of deconstruction and reconstruction. My use of materials is integral to the conceptual unfolding of my work: the process of cutting, collage, photo-montage, staining, sewing and stitching – and their association with women's practices – are refined and reassessed in the context of each installation.

The Exquisite Pirate project initiated from a simple question – "were there any women pirates?" Parallel to this was the seemingly huge growth in popular culture imagery connected to pirates and continuous reference of the word itself in the media as relating to cyberspace activities. In contemporary and historical Australia the boat and ship have loomed large around immigration issues and for me have become expressive, powerful images for postcolonial discourses.

Of my research on women pirates, it is Kathy Acker's book Pussy King of Pirates that resonates through The Exquisite Pirate. Acker uses the metaphor of female pirates to explore feminine issues and sexuality, at the same time subverting the historic perception of piracy as a male domain.

Sally Smart