The River Flows East for Thirty Years and West for Forty: Understanding Our Conflicted Relationship with Literati Culture

By Rebecca Catching

China has gone through waves of embracing its traditional culture then rejecting it — a complicated dance between ancient values and Western modernity — one which endures today. Before we embark on the artwork, it seems relevant to provide some historical context to China’s alternating embrace and rejection of different sets of values.

As early as the May Fourth Movement, we began to see a questioning of the relevance of traditional society, Confucian values, and the family structure. Wu Yu, one of Confucianism’s most vigorous opponents, described the Confucian doctrine of filial piety as “a big factory for the manufacturing of obedient subjects,” and he described Confucian ethics as “man-eating mores.”

Writing in 1916, Chen Duxiu criticized the hierarchical Confucian relationships based on a binary model of “superior /inferior,” as being “incompatible with the modern idea of equality.” 1

But there were others, who felt that indigenous Chinese concepts should form the bedrock of Chinese society and promoted guoxue (the study of ancient Chinese culture) as early as 1905. Figures such as Liu Shipei, himself a scholar trained in guwen or classical Chinese, promoted classical knowledge through the Association for the Preservation of Classical Chinese Learning, which published a number of textbooks and the Journal of National Essence — a scholarly publication which included both articles on Qing thought and the European Renaissance. 2

This interest in traditional culture, however, was partially motivated by the desire to criticize Manchu rule as according to the myth of the Yellow Emperor, the Manchus were not considered part of the Chinese community and writings by Liu Shipei and others exploited this myth. As John King Fairbank and Denis Crispin Twitchett have stated:

These [writings] offered a definition of the Chinese peoples as a place, blood, custom, and culture. All of them pointed to some antique point of origin for the complex of national values which might provide a key to the restoration of polity and culture today. 3

In a sense, Liu and his compatriots were not only providing a basis to reject Manchu rule but also to legitimize themselves; since they had lost their social status due to the abolition of the civil service examinations. While they spent plenty of time with their heads buried in ancient history books, some literati tried to use “guoxue” as a way for understanding Western ideas and the modern realities. For instance, Liu used his research on the Western Zhou Dynasty to examine the similarities between Western and Chinese political systems. 4

Also at the turn of the century there emerged another Neotraditionalist movement called National Character or guoxing put forth by Liang Zhi’ao, National Character was a liberal brand of Confucianism which put emphasis on reciprocity (shu), “respect for rank,” (”mingfen“) and concern for posterity (“luhou”). Liang encouraged a sense of self-sacrifice and a mild liberalization of the typically rigid Confucian relationships yet at the same time underlining the traditional importance of the family. 5

After the founding of the country in 1949, the pendulum shifted; traditional values and culture became distinctly unfashionable. With the 1966 movement to “Smash the Four Olds” representing the height of anti-traditional rhetoric in China as described by Jiang Jiehong in “Burden or Legacy: From the Chinese Cultural Revolution to Contemporary Art”.

Red Guards searched over 10 million homes across the country and confiscated or destroyed ‘old’ property, including dynastic calligraphy and paintings, ancient books and archives, gold, silver or jade ware and jewelry. In the city of Ningbo alone more than 80 tons of books from the Ming and Qing Dynasties were pulped. Most of the idols — including statues of Buddha, folk gods, even Confucius — religious architecture, frescoes, and books failed to escape this cultural disaster. Records indicated that there were 6,843 cultural relics registered in Beijing in 1958, but only 1,921 remained in the 1980s. 6

Still, despite the political climate, traditional culture did survive, enjoying a somewhat clandestine existence. Chinese “guohua” (ink) painters still practiced their trade to some extent, some used guohua to depict revolutionary subject matter, while others produced works for private clients or worked in the privacy of their own homes, receiving financial support from relatives.

The Reform and Opening Up removed most restrictions on traditional culture and now, almost 100 years later, China is once again re-negotiating its relationship with traditional culture with a second wave of “guoxue.”

This guoxue movement, like the first one, is not completely divorced from politics, but it also speaks to a genuine interest in Chinese culture after the recent storms of modernization.

The current guoxue craze involves everything from government granting of days off for traditional Chinese holidays to the Confucius Institute, China’s arm of soft power abroad. Writer Norman Ho, discusses the growing guoxue craze,7 mentioning the prominence of Confucius at the Beijing Olympics, the recent government-funded biopic of Confucius directed by Hu Mei and the mammoth Qing History project:

In 2002, the government pumped about US$75 million dollars into the project, which has engaged more than 1,600 scholars from research and academic institutions across the country. The completion date is set at 2012, and it is estimated that the new history, which will also be translated into various languages and digitized into databases for global dissemination, will contain over 30 million Chinese characters and take a doctoral-level graduate student approximately 10,000 days to consume the material.

This act was, in fact, common of new dynasties, which would frequently invest time and money into creating a record of the previous dynasty, thus situating themselves in the long line of history.

Then there is the international interest in Chinese culture — which is being fueled in part by the Confucius Institute which has 316 branches worldwide. The institute focuses mostly on bringing Chinese language teachers to public schools and universities — one article by Xinhua brags that a remote learning class helps children in mountain areas of the US learn Chinese. There is also the “Da Zhonghua Wenku,” a series of bilingual editions of the classics which enable foreigners to learn about traditional Chinese culture — a series which has been praised by Wen Jiabao.

Though enthusiasm for these cultural initiatives abroad is often tempered with suspicion, and we must always be wary of the politicization traditional culture, the opportunity to learn more about Chinese culture is in itself not a bad thing.

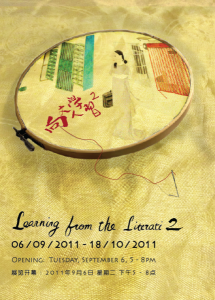

Given the recent popularity of guoxue, it seemed appropriate to re-visit out “Learning from the Literati” series and view these ideas afresh regardless of their political associations.

In this show we hope to allow you to re-visit these artists in their scholar gardens and explore some of their values, ideas, and lifestyles — what lessons can we take from them when we re-enter the modern world?

Shi Jinsong offers us a succinct metaphor with a sculpture composed of a piece of rubble, which has been drilled with holes so that it looks like the traditional “scholar’s rocks” found in Chinese gardens. In the past stones were originally brought from Tai Lake near Suzhou and were prized for specific qualities: thinness, openness, perforations, and wrinkling.

The significance of this rock in a garden is that it can represent a mountain and help create the illusion of a vast landscape within the confines of a small space, explains Richard Rosenblum:

The French scholar Rolf Stein stated that early Chinese believed that somewhere in the highest mountains there was a cave that was an exact representation of the world outside. In its center was a stalactite that gave off the milk of contentment . . . this inward focus shows that Chinese culture looked for paradise inside of things, just as Western culture looked upward and outside. In Chinese art, this orientation caused a search for ‘a world within a world,’ for imagery in surprising and unpredictable places. 8

Shi Jinsong captures this idea of a world within a world in this work by creating a craggy peak of a piece of a chunk of bricks fused together with mortar — the kind of rubble which we find strewn across urban landscapes all over China. The name of the work, “Beifu No. 525” is the address of his former studio which was demolished. This title conjures up a number of interesting meanings: the itinerant life of Beijing’s artists (constantly trying to dodge various wrecking balls), the destruction of important urban communities and the disappearance of ancient values and culture.

At the same time, he offers us hope in the idea that beauty can be found in even the most ruinous corners of a city. In his artist statement he writes, “If we see a beautiful vision, does it matter in whose courtyard we see it?” Here he poses the question: “Do we need to be in a garden to find beauty or should we search for it within our everyday lives, no matter how decrepit.

Shi Jinsong’s artist statement was actually written in a classical Chinese style, a poetic string of images which alludes to “Travelling in the Garden·the Dream Interrupted,” lyrics from the Peony Pavilion. This reference alludes to his previous work “Peach Blossom Prose,” 2009 shown at Platform China in Beijing.

In this work, he staged an ancient Chinese feast with delicacies and several different kinds of peach wine. The centerpiece of the metaphorical table was a peach tree suspended in air, which was slowly being denuded of its bark. The peach tree, after being stripped of its bark, was later burned and brought to Shanghai for a separate performance.

“A play named ‘Peach Blossom Prose,’ was staged here last year. Everything which used to be alive (peaches and good wine) will be gone in time, leaving only is a dry well and wretched walls.”

The peach tree is a symbol of longevity, and his transformation of it, first killing it by uprooting it, then stripping it naked, then burning it, he performs a purposely-destructive act in a ritualization of the destructiveness of urban gentrification which is occurring all around him. Yet “Beifu No. 525,” asks us not to lament the changes in society but to make beauty out of what we can find — to turn wretched walls into scholar rocks.

Japanese artist Sayaka Abe is also fascinated by the miniaturization of landscape. Her work “The Imaginary Mountain and Fighting with Water,” 2010 captures a kind of poetic infinity — a landscape of the imagination which mimics shanshui painting but places it in a modern context. Using layers of chiffon as her canvas, Abe applies lino-block prints to create images of typical Dutch row houses, piled higgledy-piggledy into the hold of several ships. The ships, with their mountains of cargo, are staggered and recede into the distance, creating the sweeping illusion of distance typical of shanshui paintings. Between the mountains flow rivers of thread, blue and yellow stitches which perforate the white silk, at the same time an aura of blue is lent by pieces of green and blue silk stitched on to the back of the work.

Abe is originally from Japan, a land of mountains, but is currently living in Holland, a country where 27 percent of the land is below sea level, which is constantly fighting to keep water at bay. Her cloth sculpture exploits this tension to explore the relationship between man and nature and the consequences of global warming.

In literati painting, man is always a small figure struggling up a giant mountain, a minute element in a grander sphere. Contemporary society has reversed that balance: creating dams and dikes, roads and quarries, changing not only the surface of the planet but also the composition of the atmosphere. Here, Abe predicts a future for humanity where we will be forced into Noah’s Ark in order to escape the rising tides. Abe’s little boats look like small, overcrowded bonsais — miniature worlds, which are actually full-sized worlds crammed into an incredibly small space.

Water also plays a big role in the work of Qian Rong. His previous series “Spy Movies and Local Snacks,” 2009 which showed in “Re-visioning History” situates itself along the Bund — a symbolic site which marks the beginning of the semi-colonial Shanghai (and an introduction to many Western ideas) but it is now dwarfed by Pudong — the symbol of China’s financial prowess. Qian Rong is fascinated by the city’s waterways — canals and rivers which once wove an extensive network through the city. Zhaojiabang Lu was once a canal and the areas of Dongjia Du and Tanjia Du, which were named after ferry crossings, all which speak to the importance of water in Shanghai. Qian Rong frequently visits the canals, creeks, and coast on his scooter, exploring river life and fishing communities.

In his new series, “Lu Xun Boat” 2010, water serves as a metaphor for history and the passage of time, which was a key concern for literati. Confucius described time as something which is fleeting, something which passes — like a constantly-flowin river. And Daoists held the passing of time in high esteem, as something that passed by and went far away, then returned again in a cyclical fashion. 9 This cyclicality is summed up by the ancients’ concept of time: a concept which was more in tune with nature, and which connoted a sense of “timeliness” or seasonality, rather than the modern concept of time as something that can be measured in precise increments.

“Spy Movies and Local Snacks,” explores the cyclical nature of history, says the artist, “We eat the same things (xiaolongbao pork dumplings in this case) as we did 50 years ago and that the same structures and relationships that existed before also exist today.”

“Lu Xun’s Boat” reflects this concept of the cyclicality of history with an image of xiaolongbao, painted in a somewhat naive style. The sculpture is a hybrid figure which is half cargo ship and half man. The man’s torso is glued into the hold of the ship as he stares steadfastly into the distance like the great helmsman. The man’s back is supported by a pagoda — signaling the history and culture which are behind him and the image of Lu Xun on his chest.

Lu Xun provides an interesting symbolism as he is often associated with the May Fourth Movement, which criticized many aspects of traditional feudal society. Yet he was principled and rebellious, unafraid to voice criticism — qualities he shared with the literati.

China’s early years as a republic were fraught with these kinds of contradictions; it was a confusing time when Western technology, ideas, and consumables are flowing in but the interest in guoxue nonetheless remains strong. Qian Rong’s figure is stiff, as if paralyzed by this temporal schitzophrenia and the decisions he must. “The river flows east for thirty years, then flows west for forty,” says the proverb, but how do we know which direction we should paddle?

Issues of globalization, consumerism, and modernity have always been central to the practice of Chen Hangfeng. His work “Santa’s Little Helpers,” 2007 addressed the globalization of Christmas in a small village near Wenzhou. While his “Logomania” 2005-2008 series looks at the encroachment of international brands onto our urban landscape. But in the “Four Gentlemen,” he tackles issues of globalization on a more metaphorical level. The work consists of four unvarnished wooden boards upon which are pinned strips of recycled plastic cut to resemble images of classical Chinese bird and flower paintings. Here Chen replicates the “Four Gentlemen,” the orchid, plum blossom, bamboo, and chrysanthemum — plants which were valued because they possessed the qualities of a model gentleman.

The bamboo is prized for its strength as a plant that bends with the weight of the snow but is flexible and doesn’t break. In this way, it is seen as something strong and principled, yet at the same time humble possessing a sense of inner tranquility.

Overcoming the hardships of nature/society is a prominent characteristic of the four gentlemen. We can see this with the chrysanthemum, a hardy plant, which can weather frost and snow. It has the courage to bloom even though winter is coming and is therefore seen as a plant that is brave and defiant.

We see this bravery as well in the plum tree — raised for its hardiness — one of the first plants to poke out buds while the ground is covered in snow — it symbolizes the hope and faith that Spring will eventually come.

The appearance of the orchid, sprouting up leaves and producing delicate, yet striking flowers, signaled for the literati the beginning of spring. Yet orchids are a rare find and the flowers are often hidden shyly amongst the leaves. The orchid, like the literati, live a lonesome existence and the lesson that the orchid teaches us is that one must strive for moral and artistic excellence even if there are no spectators. In this sense, the orchid represents a sense of grace and moral purity.

Chen Hangfeng’s reconstructions of these plants are based on the book “Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden” 1701, an ink painting primer. His reference to this book points to the guoxue craze and the concept of “learning” about Chinese traditional culture. At the same time, by making “the gentlemen” out of plastic bags — bags often procured on shopping excursions — he is expressing the faddish nature of this craze and the often-superficial forms it takes. The plastic (a crude un-refined material) hints at the impossibility of returning to the literati garden. His mounting of the plastic with straight pins is also symbolic — like an artifact in a display case — literati culture is something that is already in a sense dead — wiped out by the process of modernization.

Girolamo Marri, an Italian artist based in Shanghai, has often tackled the confluence of Western and Eastern culture in his works — looking at the post-colonial implications of this dialogue.

In his video work “Opinion Poll” 2008, he roams around the lanes of the 798 art district asking unsuspecting passers-by to participate in an opinion poll. Bundled up in a thick winter coat with a shock of unruly white hair, the artist presents his subjects with a “microphone,” which is actually a lint roller brush and asks them innocuous questions like: “What do you think of Chinese contemporary art?”. When they attempt to provide an answer, he takes the microphone back and proceeds to give the audience his own opinion on the subject. This and other projects such as “Dear Chinese Friend, Learn to Make Coffee the Italian Way,” 2008 explore the one-sided nature of many cultural dialogues.

In Marri’s work, he often stars in the role of the arrogant, clueless Westerner — whose behavior becomes increasingly absurd. His latest project “What Did I Learn from the Literati,” 2010 also has the artist “in character” and attempting to reach a new mental plane through a commune with nature.

The three-channel video installation features two different modes of filming. The first two segments are shot in a mockumentary-style, where Marri takes on the role of a “character” discussing his attempts derive wisdom through a commune with nature. He recounts a humorous story of his separation anxiety with his mobile phone and laptop and whinges about buzzing and biting insects.

In the second segment of the documentary, the artist recounts how upon returning from nature he made it his mission to pass his newfound wisdom on to others. The result of these attempts is frustration at the inability to effectively communicate and the lack of interest on the part of his audience. We see the character work himself up into a complete frenzy over his failure and eventually come to the conclusion that “we can learn shit from the literati.”

Close-ups of his face, revealing tormented expressions — show a portrait of a person who is in a sense “too far gone” to ever be able to reach any state of mental peace and clarity. Here Marri is not only playing on the Western appropriation of Eastern spiritualism and the world of self-righteous proselytisers but the attention economy which makes us enslaved to our gadgets making any attempt at hermeticism impossible.

At the same time, he is calling into question the wisdom of the hermit lifestyle. Is going off into the mountains not an act of selfishness, a cop-out? In discussing his project Marri questions what we really can learn from nature. We do spend 99 percent of our time in society; couldn’t we learn more from working in an office for a year and learning knowledge, skills and an understanding of how to deal with other human beings? What kind of actual strategies for dealing with human beings can we learn in the outdoors classroom?

The last segment of the video features the madman artist — who as if driven over the edge by his isolation and then his failure — is dismembering a flower. By proposing a foil to the idealized figure of the literati — Marri warns us about the dangers of nostalgia — and urges us to really think deeply about the ideologies we espouse, and our human obsession with finding a panacea to all of our existential ills.

Ji Wenyu and Zhu Weibing are also interested in issues of man, his environment and his own mental space — a theme which they’ve been exploring since 2005 with their cloth sculptures “Enjoy Flowers,” “Watch the View,” “In Garden & Out Garden 2,” (all 2005) and more recent work such as “Edge of the Pool,” 2008. Typically these works depict individuals attempting to commune with nature with varying degrees of success. In “Enjoy Flowers,” a group of men stare reverently up at a flowering tree, while in “Watch the View,” a young boy grasps his balcony as he stares off at a fantasy traditional mountain landscape.

“In Garden and Out Garden” reverses this relationship of looking with a group of people stuck in a crowded courtyard staring out the window at the world outside.

With “Watch the View,” there is a pronounced sense of distance or unattainability with the people attempting to commune with a version of nature — which is actually not nature but something artificial and manmade. Their latest work “Feat of Humanity,” 2010 conveys a similar sentiment with a man sitting astride a rock gazing up at a waterfall constricted by a brightly-colored electricity dam.

Though the artificialization of nature, dates back to the scholar gardens of literati times, the artists are looking at a modern problem of large-scale infrastructure projects and their impact on the environment.

The artists date the current fixation with shaping and controlling nature to suit the energy needs of the country back to the May Fourth Movement, where a country suffering from insecurity due to the encroachment of foreign powers, took readily to ideas of scientific progress, regardless of the impact on the natural environment. “After 1949, this kind of thought was expanded, and leaders adopted the idea that, ‘with determination, mankind can conquer nature.’’ Earth-shaking changes soon happened in China,” write the artists. These changes entailed actual tremors caused by dams, the loss of communities and cultural relics, and ultimately a loss of identity.

This sense of helplessness is expressed by the figure sitting on the rock — dressed in non-descript clothing, with no facial features. The man stares up at the staggeringly impressive scenery in front of him — majestic mountains are made out of natural, hemp-colored linen, folded to resemble the creases of an ancient limestone peak. From the dam flows a fine gauze of water, which cascades to the ground and billows around the rock. The artists have perfectly matched the hues of the piece so it looks like a Chinese landscape painted on aging “xuan” paper, but they highlight the anachronistic presence of the dam with green and pink fluorescent markers which scream out in hysterical colors disrupting the scene.

Chinese landscape paintings are typically known for their sparing use of color and Shi Jing has taken this concept to the extreme, not using any color per se, but relying solely on the texture of the black paint, coaxing it into ridges and grooves which pick up the rays of light and thus create an image through these captured slices of light.

Shi Jing began working on landscapes in 2000, when he would often return to his home in Yunnan and paint the mountainous landscapes at the foot of the Himalayas. Sometimes he would go out and paint in nature but mostly he worked from photographs. In his essay about Shi Jing’s work, critic Edward Lucie-Smith discusses the relationship between photography and painting:

We see that the source material is almost certainly photographic. Chinese ink-paintings of mountains are never literal — they speak in metaphorical terms about the emotions such landscapes evoke. Shi Jing is aware of the way in which photographs often tend to turn the sublime into the banal. By making us look at his mountain-scapes obliquely, he aims to restore some of their mystery — one might say, he uses tricks to give them back their magic. 10

Often, the act of painting for Shi Jing was about understanding the essence of the landscape — a concept central to literati painting. Says the artist, “At the time, I chose subjects in Yunnan in order to learn to recognize my environment again. There are no special elements in these scenes, but still, the landscape nonetheless gives us a feeling with these big mountains and small mountains. I would often just paint water. Is this seawater, river water or lake water? We don’t know just that it has the nature of water.” 11

This interest in the “essence” of objects is deeply in line with literati thinking. Daoists believe that part of understanding an object is understanding the way in which it changes — Shi Jing captures this metaphor in his work by forcing the viewer to pivot in front of the work in order to see it from all its angles and incarnations — the appearance of the forms literally changing before the viewer’s eyes.

This idea of learning through observation was espoused by Confucians as well, who thought that travel was crucial in understanding the world. Landscape painting, in a sense, was an extension of this idea of traveling.

With Shi Jing’s work we are not necessarily traveling to a particular place but to a state of mind — a kind of existential plane filled with empty voids where we can ponder the vastness of the universe.

Here, Shi Jing’s choice of the pine tree is symbolic. In literati culture, pines embodied a sense of peace and longevity. The pine grasping onto a cliff — persevering against nature was symbolic of the literati himself — wiry and emaciated, the literati endured a hermetic lifestyle in search of inner truth. In Analects, Confucius uses the term, “hidden dragon” to emphasize that a man must develop moral cultivation before he is ready to join the government. 12

Gao Mingyan looks at the literati lifestyle as but fuses it with a much more quotidian aesthetic. In this case, he’s focusing more on the element of freedom. The literati had a tendency to overturn conventions; they would go on wild drinking binges, take medicinal herbs, which would invoke hallucinations, and would often take Daoist rituals and purposely perform them in the wrong way. The goal of their existence was personal expression through any means possible and sometimes in the heat of the moment, while painting, they would seize upon a blank wall and write down a few lines of poetry or sketch a painting on the seat of a chair. In some ways, their actions were very modern — artists such as Rauschenberg would be impressed with their use of found objects and their hijacking of Daoist rituals. If placed in a contemporary context, could easily be seen as performance art.

For them, life and art were as inseparable as night and day. Something that they lived, ate and breathed. In “Glittering Space” 2010, Gao Mingyan has collected a variety of objects that date to the Reform and Opening Up period and he has perforated them with a needle as to create a filigree of small holes. A small LED-light placed within the objects creates a pattern of light (almost like an astrological chart), which emerges when the objects are placed in the dark.

Using these objects, Gao Mingyan reconstructs a-seemingly banal room filled with references to great masters of traditional painting. While the original masterpieces inspire awe, his masterpiece-inscribed-objects evoke a charming naïveté. The Guangming brand milk carton inscribed with a simplified image of a pagoda shows how, within the garish visual culture of contemporary society, we can still find a sense of beauty and grace — much in the same way that Shi Jinsong constructs beauty out of a piece of rubble.

The use of objects from the Reform and Opening Up is also significant because it represents a time when China was at a crossroads between a strong socialist culture and a more international free-market culture. In the darkness of the room, we don’t see the dated furniture and consumer goods (a lifeless material existence) but an inspiring constellation of lights piercing through the darkness and reminding us of the wisdom of literati thought and values.

So what can we say we’ve learned from the literati? That man needs to learn to respect his relationship with the environment (Sayaka Abe and Ji Wenyu); that globalization and traditional culture have a conflicting relationship (Chen Hangfeng) and that going back to a literati mode of life is perhaps a futile endeavor (Girolamo Marri). We’ve learned that time is cyclical and history flows both ways (Qian Rong). We’ve learned that one can find at least temporary peace in nature and deep philosophical contemplation (Shi Jing) and, finally, we’ve learned that beauty can be found in the most mundane places with the help of imagination and creativity (Shi Jinsong and Gao Mingyan).

August 26, 2010

1. Wing-Tsit Chan, Hu Shih, and Chinese Philosophy, Source: Philosophy East and West, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Apr. 1956), University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 3-12

2. Tze-Ki Hon, The Yijing and Chinese Politics: Classical Commentary and Literati Activism in the Northern Song Period, 960-1127, pp 96

3. John King Fairbank, Denis Crispin Twitchett, The Cambridge History of China: Republican China, 1912-1949, Volume 12, Part 1.

4.Tze-Ki Hon, The Yijing and Chinese Politics: Classical Commentary and Literati Activism in the Northern Song Period, 960-1127, pp 94-98

5. John King Fairbank, Denis Crispin Twitchett, The Cambridge History of China: Republican China, 1912-1949, Volume 12, Part 1, p363

6. Jiang Jiehong, Burden or Legacy: From the Chinese Cultural Revolution to Contemporary Art, Hong Kong University Press 2007, p64

7. Norman Ho, Unlikely Bedfellows: Confucius, the CCP, and the Resurgence of Guoxue, Agriculture, Vol. 31 (2) – Summer 2009 Issue

8. Richard Rosenblum, “The Symbolism of Chinese Rocks” from Hu Kemin’s book, The Spirit of Gongshi: Chinese Scholar’s Rocks.

9. Gao, Ming. Commentaries on the Silk Scroll Book of Laozi, Boshu Laozi Xiaozhu. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1996

10. “Shi Jing” Edward Lucie-Smith, Dharma Garden, OV Gallery, 2008

11. Interview with Shi Jing conducted by phone in August 2010.

12. Tze-Ki Hon, The Yijing and Chinese Politics: Classical Commentary and Literati Activism in the Northern Song Period, 960-1127, p82

向文人学习2

林白丽

站在一个外行的角度, 以现代的眼光来看, 中国传统风景画似乎是一个越发坚硬的连续体 - 变化量超千年之久。1 但在柔和的色彩以及优雅的线条下面, 有一些更为激进的东西。绘制山、鸟、花的画家谓之文人学者或文人, 他们为求建立一种将画面作为自我表达, 风景画作为精神的象征的绘画形式而脱离了宫廷画的固定模式。

这些人是文官考试出身, 对儒教、道教、佛教经典娴熟于心。他们可以死记硬背上百首诗, 是杰出的学者、诗人、画家、书法家和音乐家。

陈继儒, 晚明时候的文人, 列出文人活动的清单:焚香、品茗、修订书籍、赏月、午睡、 拄着拐杖行走、制药、远离尘嚣。2

虽然经常参与政治, 但他们与宫廷的当权者有差。尽管他们关心盛衰但多数的文人都因未通过文官考试而无法正式地参与政务。

晚明时期, 人们开始对描绘文人以及他们生活习惯的书产生了兴趣, 关于他们如何赏心美雅地或与世隔绝地活着, 比如在一个远离文明的山顶。这些书变成许多城市居住者的喜好。3

带着思考, 我们开始寻找艺术家来参与我们第二期向文人学习的展览。如同第一期, 我们有一批对文人传统满怀敬意的艺术家 - 通过参考经典的形式与观念来表以崇敬之心 - 与此同时艺术家们也探索了现代社会和文人价值的冲突。最后我们仍有艺术家关注与这个千年的旧文化建立联系的挑战性 - 这个历史的鸿沟太深所以无法克服吗?在如此多的变化中, 我们仍然尝试去保有一些形式的有意义的对话。

让我们从一个带着对传统的崇敬, 悉心钻研哲学和历史特异性的艺术家开始。夏国在作品中完成了他的想法。“义竹” 审视了文人与原则问题之间的战役。文人一直站在为道德问题给出建议的位置(即使有时他们的言行并不一致)。许多植物被用作代表文人特点 - 梅树、松柏、兰花和竹子, 不一一列举。

夏以竹子隐喻:仅在竹段部分, 他将棒骨焊接, 串联在钢棒上。而竹子经常是以一系列惯常形状的节段所组成, 被不同形状的骨头创造的奇怪的突出物。骨头传达了文人个性的特定象征, 骨气可以被转化为个性的主干和力量, 同时风骨暗示了相同的涵义, 但仅被在绘画和书法技法中被应用。中国文学与文化学者马爱林讨论了骨气与文人发生关联时这个术语的背景:

中国学者季羡林曾经在他的 “一个老知识分子的心声” 中幽默地对这个术语及中国文化做出了幽默的关联, 令人信服地论证了他的问题。他认为骨最能表述过去中国文人在人生历程中所经历的挫折, 最能捕获他们通常的身体形态的基本特点, 生动地, 注入瘦骨嶙峋、骨瘦如柴等等。沮丧与贫困, 他们除了他们的骨气外身无外物。然而为了正义这一目标他们会毫不犹豫地舍身取义。这样的精神叫做骨气。4

竹节的萌发, 用一些金丝做成的成簇的叶子被连接在剔骨刀上。这里夏国提及了文人极其危险的位置, 经常冒着被迫害、被流放或祸延全家的危险做出他们的批判, 而这些人以深谙儒家、道家道德观为豪, 尽管正义之路荆棘密布, 陷阱重重。

用一些金属丝做成的成簇的刀叶被连接在剔骨刀上。这里夏国提及了文人极其危险的位置, 经常冒着被迫害的危险做出他们的批判, 被迫流放或祸延全家。而这些深谙儒家、道家道德观的人却以此为豪, 尽管正义之路荆棘密布, 陷阱重重。

王韬程将我们所认为的文人生活的优雅高贵与现代生活的混乱、功能失常做出比较。他的作品精致地以墨色在宣纸上描绘, 让人不禁联想到工笔画, 而描述的内容全然是当代的。

王韬程, 一个住在德国的上海艺术家, 他身处异乡所以对传统的兴趣更为浓厚。在他的卷轴画 “一个浪漫的人” 中, 以无声和精细的线条在7米的卷轴上表达了他的怀恋之情。不同于传统的卷轴画仅绘一景, 王的卷轴被分成了诸多格段, 几乎像是一本漫画书。王叙述了他住在工人阶级60年代风格的复合式公寓力的经历, 试图像现代文人那样生活, 终日以书、诗、画相伴。王在他的作品中总是以一个不协调的因素出现 - 一个旁观者, 穿着女性或者奇装异服, 似乎在另外一个存在的时间或空间观察着另外的世界。

在他的卷轴的第一个格段里我们看到他穿着一条长款的流线型礼袍, 看起来像一条超大的文人袍, 但没有领子胸前也没有胸前的织物。王的自画像有一些奇怪的地方。这个袍子看起来像医生袍, 他看起来像个境况不佳的病人, 他的一只手尴尬地放着, 另一只手拿着一个皮箱同时他脸上的表情惊愕或沉思 - 像是一个病人逃出医院去参加一个重要会议。

“现实” 的元素被强调, 无处不在的绿色信盒和2条红色内裤被悬挂在背景中。但“浪漫的人“带着他那尴尬的手走近右边的绘画, 画中有一些雅致的开着花的树和一片悬荚的灌木丛。树下挂着一个古雅的苍蝇挂网, 招引了以大群的苍蝇, 唤起了人们对传统花鸟画中昆虫的记忆。但谁都很难在放着用以吸引腐烂食物的槽下获取任何美感。

图片里还有一些更荒谬的元素例如一条巨大的鱼忸怩作态地盯着王, 边喝酒边从一个开着的窗口处将瓶子扔到下面。

在墙壁的一边, 王写下了几行汉代诗人曹植的“洛神赋“。像上面那条鱼一样曹植是一个臭名昭著的醉汉, 但也是一个天才文人, 他可以背诵 “诗经“, “论语” , 年仅20的时候就会背诵一万首诗。在诗中, 曹植在访问兄弟期间邂逅了一个女神, 她召唤曹植过来和她一起, 当她要求曹植跳入河中时, 曹植开始怀疑她的意图。

向下指向水深处, 在那里我们可以遇到彼此。

然而我恐怕这个圣灵欺骗我。5

夜耿耿而不寐,

沾繁霜而至曙。

前面的这两首诗被画在了墙上, 第二首用墨水打了个叉。这一见到圣灵的错乱的精神状态给予我们一个有趣的隐喻关于我们与过去传统之间的关系。

视提供了一个有趣的隐喻看待我们的关系和过去的传统。它们是真实的抑或只是意图对我们做出危险的诱导吗?

这首诗提供了一个真实与非真实之间的有趣的比较, 即现实与精神世界, 反映了真实的世界(当代中国)和王在其作品中描述的非真实的 “失落的文人文化” 世界 。

当王韬程将幻想带进现实世界, 柴一茗将真实世界的元素和幻想元素融入到可以称之为超现实主义的中国风景画里。柴长期以来始终对所有文人的事物有着浓厚兴趣, 而他的笔法受到了元代画家倪云林的影响。与此同时他的构图受到另一位元代画家王蒙的启发, 以层峦叠起的山脉风景布满整幅作品, 留下微少的空白部分给眼睛栖息。

柴的绘画有近似的结构, 三维, 不平整 - 山的表面有不少层叠和涟漪。他画中的洞穴和隐秘处有许多神秘的文人石, 我们经常能看到许多有趣的惊喜, 比如在峭壁之间的空间的一个飞碟、一个在悬崖下的名人、一个坐在树下的的兔女郎 - 这种荒诞的意象经常出现在柴一鸣的水墨画中。

柴非常喜爱西方艺术、哲学, 在他的作品中有对西方文明日暮穷途的潜在暗示 - 布满藤蔓的多利克柱式、19世纪哲学家或发明家贴在山边那阴森的脸庞, 还有极为荒诞的拼贴图比如飞行着的一个巨大的碗状的粉色和绿色相间的冰淇淋。柴很小心地从杂志上剪下这些图片, 然后把它们保存在家里, 接着把它们放到他觉得作品中合适的地方。

一架在云层间飞行的飞机或一架在山顶上飞的直升机是很容易被辨认出的,但他的大多数图片都不是很明显, 需要大量的调查才能获知内容。比如覆盖在山边的鱼鳞、在密林中微微探出一个孩子的脸。 所有这些隐秘的图像是在对话潜意识和超现实, 在他对消极空间的处理中重新被拣起。这种在传统绘画中通常被留白的空间在柴的作品中找到了一个身份 - 以岩石的轮廓形成一个人的轮廓。

吴高钟带我们走近一个类似超现实的世界, 一个我们注意不到的地方。 他以一组在神圣光芒投射下的雄伟山脉的照片, 探索了乌托邦世界与文人世界之间的关联。玄妙的云带, 这些恬淡的山峰将我们承载进中国风景画平静的近乎虚无缥缈的世界之中, 但吴不会允许我们这样轻易地逃离现实。

他加入了一层批判性分析, 或更确切来说是霉菌。吴的群山是以腐烂的有机物做成的, 附着着一层米饭或面条的浆糊, 这个浆糊会被留在上面数日而显微镜下的真菌会产生近似完美的微小斑驳的叶状物。白色绒毛的遮盖虚拟了远处山顶树群的效果, 而棕色和紫色突出了其它的矿物, 给了岩石它们自己的色彩。

这些山峰都依偎在一片稠密的由棉花木条制成的雾中。虽然一些拍摄下, 这些云是纯白的, 缺乏色彩的, 通常它们会在室内黄色和紫色的投射光的缠绕下被捕捉 - 所有这一切都与荷塘绿的天空形成了对比。

与其说效果让人欣慰不如说是颇为怪异 - 也许成就了一些与模具相关的厌恶感。有机化合物的使用不仅为这些假山创造了一个惊人的有机结构, 还增加了一定量的象徵意义。比如, 参考了道教思想的人生和侵蚀。虽然真的山腐烂需要几个世纪, 这些模具山大大加快了这个进程。老子道德经第16章,解释了我们需要接受这种变化的观念,而不是拒绝它:

万 物 并 作, 吾 以 观 复。

夫 物 芸 芸, 各 复 归 其 根 。

归 根 曰 静, 静 曰 复 命 。

复 命 曰 常, 知 常 曰 明 。

不 知 常, 妄 作 凶 。

知 常 容, 容 乃 公,

公 乃 全, 全 乃 天,

天 乃 道, 道 乃 久, 没 身 不 殆 。

也许吴试图告诉我们, 不要揣着一个满是灰尘的旧时理想, 也许在那时它甚至是不存在的, 我们最好真正地拥起道教的原则:接受改变, 学会如何处理当代社会中棘手的现实。

生命的自然循环这一话题也成为史金淞的作品 “那边” 的论题。在这个作品中, 史收集了各种各样的动物骨头比如鸡骨头(从一些饭店)以及从槐树(树砍下的木材, 焚烧这些材料, 最后剩下木炭。降解这些材料的实践成为了他作品的一个重要主题。(举例说从树上剥下树皮, “桃花散” 2009)或者焚烧木头的作品 “非理想状态” 2007, “1500度” 和 “213节碳” , 都创作于2008。

总是有一种对着大自然的暴力感 - 但同时将材料从从一个状态(木头)到另一个(炭), 他参考了自然周期 - 比如受到电击,然后变成碳, 回到土壤为新的植物提供营养。这与儒教的“理“异曲同工,自然的潜在智慧 - 为这一主题史做了很多调查。

在这个作品中,史将炭化更进一步, 形成了大片的黑色细尘, 突出了大段的木炭, 创造几乎同山一样的形状。

在他的艺术家说明中, 史用了炭化的这个词, 经轮回研磨后, 这个作品突出了道教关于生命的理论和佛教对于死亡的轮回观点, 生命的循环和风景画。

焚烧木炭的灰满布在地板上就如同人们在完葬礼过后会撒骨灰(有些人会这么做, 不是所有人), 突出了生死的观念。与此同时, 炭化是墨的关键要素, 而史用研磨一词, 衍生出一个文人研磨墨用来制造墨的画面, 史用原来的材料来做一个装置, 看起来像一幅风景, 但不知何故颇为暗淡 - 道出不仅仅是对个人创造的毁坏, 而且也是对于文明(想想中国许多古建筑已不复存在因为惯用的木结构)但尽管朝代和文明反复更替, 但大自然(水川河流)是永久性是大自然的宇宙本质。

计文于和朱卫兵同样将风景作为非现实世界的象征 - 或许更贴切地说, 我们无法在当代城市景观中找到这种精神上的东西, “中国新盆景” 是由一个以石树和在石头中间的一个小公寓组成的景观雕塑。在各个方向都有不同的绿色植被萌发出来, 但这个厚重的绿色的城市都挤进一个非常小的空间看起来很像香港的城市丛林。

盆栽最初的发展是巫师或巫医外出时, 会带着真的植物, 但会裁剪掉叶子为了方便运输。这些微型植物很快抓住了精英的眼睛, 到了宋代已经存在一个繁荣的盆景文化, 不仅有盆景树而且还有山水盆景 - 大片山的微型景观。有时, 它们可能简单得就像大理石平板上的石头一样。

这些景观是在不朽的领域上做成的, 自然但神秘的景观比如蓬莱山, 根据 “山海经” 所写那是神仙住的地方。这些景观为信徒在家中献祭品提供了方便, 无须长途跋涉去到著名的佛教遗址。

在他们的作品中, 计和朱将神圣不可侵犯的神灵变成了可亵渎的, 或许今天的神仙更喜欢山顶上的高端公寓。与此同时, 盆景的观念是对沉思的一种辅助, 也是对公寓大楼的加入提出疑问。我们可以在有棱有角的建筑物上沉思吗?它对我们的神经同样有镇静作用吗, 可以鞭策我们进入更高的精神层面吗?

不同于宋代的时候, 我们的实际景观是建立在我们城市混泥土的密度上而不是石灰石山峰上。也许我们有需要放弃这些不现实的理想, 因为它们与我们当下的现实已经几乎没有关联性了。

倪有鱼在他的木刻系列 “标本柜” 将盆景的观念转化成一个博物馆的标本展出, 在这里我们看到了它和盆栽的有趣的相似性, 而这个博物馆的标本展出将我们带到了特定的领域, 或者虚设(神住的地方), 或者真实(想想博物馆的标本展示出原始人如何生活)。盆栽更珍贵, 但没有将眼前的景观与观众隔开的玻璃盒子, 倪的标本距用一个玻璃柜子创造了一个历史与现实之间的距离。

在 “标本柜 之一” 我们看到一个粗糙的山景, 类似于王蒙作品中的那些, 树从缠着一条蛇的石头中猛推出来, 在蛇的周围又一系列的字母和数字, 这种人们可能在图解里看到, 像是一个地图图例一旁正解释每一个字母。

所以这里一些东西唤起了我们对放在科学知识帝国主义里的中国传统文化的一些记忆 - 前提是传统的价值被封闭而也许被纳入了科学现代性里 - 这个趋势植根于五四运动里。“标本柜 之二” 给出一个甚至更为悲观的视点, 以一个相似的山景, 这次的标本是一个有蹄的动物, 四脚朝天地在溪流上漂流, 现在的姿势是跌下山去。

将标本放在盒子里作为一个被动的研究对象这一观念在陈航峰的雕塑作品 “不许动” 2011中也得以体现。标题给出的是一种劝诫, 就像博物馆里的保安要求一个人别靠近艺术品, 也指向了观众与作品之间的紧张关系。这个作品由一块描绘着一棵松树的传统水墨画的木板组成。松树的针叶事实上是从塑料购物袋上剪下的小片黑色塑料, 然后钉到板上。大头针给出一个视觉参考, 通常它用于固定昆虫和其它标本, 创造了一种悬念。

当观众走近作品, 传感器会使风扇开始运作, 这样塑料的松树针叶就在风中沙沙作响。

以这样的方式, 我们见证了中国传统文化只有在我们所做的安排下才能存活着 - 阅读经典著作、学习诗歌或练习书法。我们的目光离场, 它们也跟着变得毫无生命力和静止。

虽然对中国传统文化的追求已经成为政府的主要目标, 作为其软实力的主动权, 通常对传统只有一个有限制性的表层的理解, 而甚少有人愿意深入研究佛教、道教、儒教的哲学和观点 - 也许他们害怕他们会找到的东西。表面的观点是反映在光滑的塑胶袋上的 - 空无一物或者被包裹着, 金玉其外而败絮其中。

我们也看到对于传统文化的业余理解 - 在作品的一些地方, 我们看到艺术家被娴熟的技巧, 也看到另一些作品上有掉下来的颜料, 增加了一层荒诞意味, 似乎这棵树是在为一些失去了再也寻不回来的东西而哭泣。

苏畅在她的照片系列 “未名山” 中也取用了这一观念, 苏住在松江 - 松江派的发源地, 明朝时期文人派系的温床。在这个系列中她试图解决文人文化与当代现实之间的关系, 建立一种磨损—尽管是建立在有目的地在边缘磨损的基础上。

在 “未名山 之二” 中, 苏畅在一张棕色桌子表面以起伏的线条摆放了几块地块, 用以模仿山的轮廓。与精心整修的世博草地不同, 苏的草坪包含了很多物种包括三叶草、棒芒草和其他杂草。这些杂草也许就是社会一些不被需要的群体的象征 - 与此同时这些植物却有明确的审美情绪。在自己的权利下它们是美丽的, 具有如纵横交错的松柏的野性。尽管文人的野性被种下 - 以同样的方法想一想松树的枝叶被金属丝紧缠绕, 看起来像被风和时间弯曲了一样。我们当下的现实是不受束缚的野性 - 混沌相伴着一个在变化中阵痛的发展中国家。

在 “未命名 之一” 中我们也看到了同一种困窘的尴尬, 一系列的塑料山被放在石板灰的水泥地板上。山顶有许多不同的地形, 但他们的边符合几何的规则, 像直直的方糖。在这里苏用她工作室手边的材料(这次是石膏)去唤起过往的一些事情。而文人画是以特定的一套知识和道德观创作的, 我们当前社会所倡导的理性价值观也许也许仅有能力生产规整的几何形状。结论是当我们已经远离了那个特地国内的时间、地点、哲学和价值观, 也就几乎不可能像文人那样地创作。

王平在他的作品 “意象风景” 中也采用了几何这个概念。这个素描系列是由紧密的线条组成, 不同形状的灰色阴影, 创造了锯齿状的山顶的效果。

这些尖状物是很危险的(想想夏国的竹子)凑近看类似一把刀的锯齿边缘。所有的这些都与以野性和表现力而闻名的文人画做了很有趣的对比。多数文人都有富足的时间作画因为他们并未通过文官考试所以他们并不为宫廷服务。在他们的作品中我们可以看到线条的野性, 这一切可能源于他们在泄气和被边缘化的状态下。

如同苏畅的山, 王的山峰的顶部也是锯齿型的, 带着野性, 完全由垂直的线组成。6

它们看上去像是被机器人或机器绘制的 - 或者也许是一个被束缚的人 - 被吸干了他的战斗精神。

“意象风景 之二” 展示了类似的冲突的意象。王再一次用他的直尺来创造一个竹茎的图像, 但这个竹茎的节段是由不羁的纠缠而野性的线条组成。这些竹子看起来像被铁丝网缠绕而窒息。竹子通常是文人的一个传统象征, 代表了力量和韧性。(比如在各种艰难情势下的隐忍)然而它里面是空的, 被视为谦逊的象征。在这些传统符号之间的威胁感创造了浪漫理想化的精神文化与高效现代社会中径直的科学线条之间的冲突。

希望通过这次展览, 我们都能从文人处习得一些什么 - 他们对自然的理解、独立而批判的精神、对于简单生活、书籍、艺术和音乐的热衷。我们看到了他们坚定自己的原则, 拒绝改变。但与此同时我们发现有一道鸿沟, 划分了我们与他们之间的时间距离, 我们要切忌不能对他们持有理想化的解读、肤浅

- 一些人将文人画的时间追溯到公元前321年

- 江南位于长江三角洲的南面

- Daria Berg 和 Chloe Starr: 中国的附庸风雅: 超越性别与等级的沟通,

劳特利奇: 纽约, 2007

- 马爱林 “中英文文化解读: 对当代文字选集翻译与释义过程中的问题研究” 博士

论文, 交流部, 语言文化研究院, 墨尔本, 维多利亚大学。

- John Minford, 经典中国文学翻译选集, 哥伦比亚大学学报, 纽约和香港大学,

香港2000

- Zhou Zuyan, 明末清初文化的双性混合, 哈佛大学学报, 美国, 2003